“After I have eaten up my cat, and made myself a muff from his skin, I must then die of hunger.”

“Puss in Boots,” Charles Perrault

The cat, who heard all this, but pretended otherwise, said to [his master] with a grave and serious air, “Do not be so concerned, my good master. If you will but give me a bag, and have a pair of boots made for me, that I may scamper through the dirt and the brambles, then you shall see that you are not so poorly off with me as you imagine.”

Anyone who knows me well knows that I LOVE cats. I can’t even say exactly why. Maybe because cats are the perfect combination of elegant and cute? Because they’re independent? The fact that they lie in the sun? Or fit perfectly into any box? Or that their not-so-easily-won affection is totally worth the effort? I can’t say, but I do understand why cats have a reputation for cleverness in fairy tales.

Perhaps the most cunning animal companion of all the talking animals is Puss in Boots. The OG animal sidekick who turns his poor master into a wealthy man. This fairy tale is definitely one of my favorites. So why don’t we take a tour through the many different versions and many possible messages of this feline-centric story . . .

In Case You’ve Forgotten Puss in Boots, Here’s a Refresher

The most popular version of Puss in Boots is the French one. Also known as “The Master Cat,” this story is one of many famous fairytales in Charles Perrault’s collection, the same author who gave us the glass slippers in Cinderella. Apparently this Frenchman had a thing for fairy tale footwear—and social climbers.

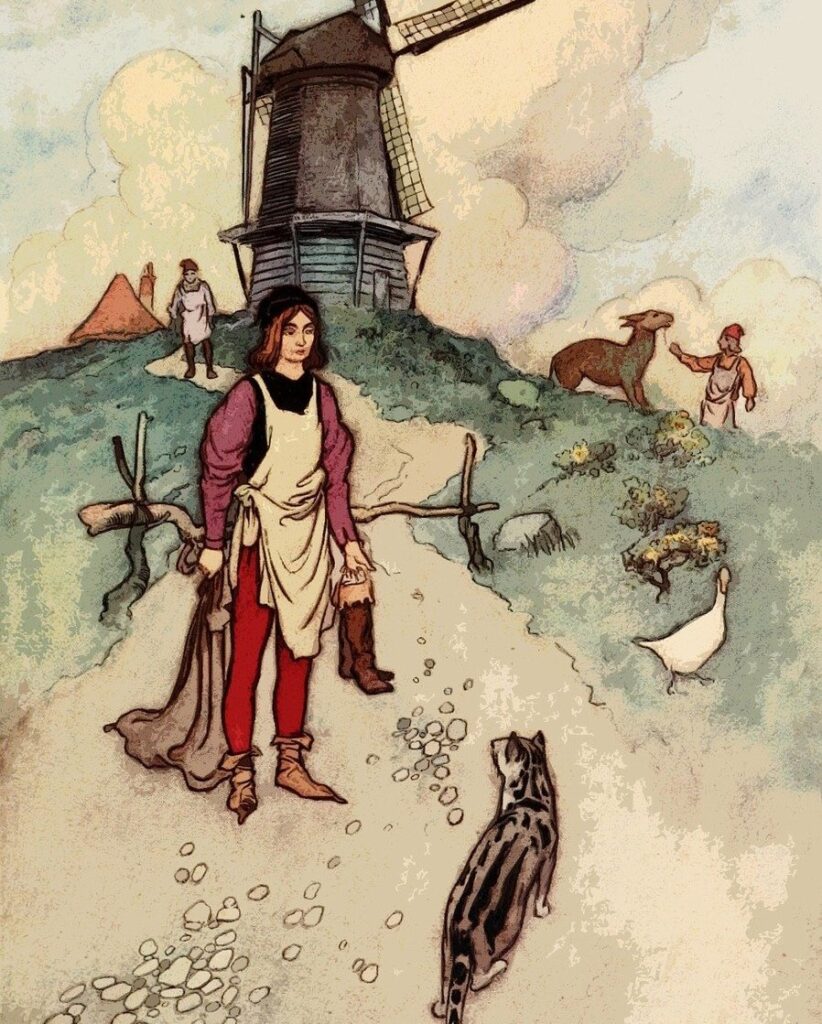

This story starts when a poor miller dies and leaves his only possessions to his three sons. The mill goes to the oldest, the donkey to the middle son, and the cat to the youngest son. Obviously the youngest kid feels cheated. Both older brothers can make a living off their inheritance, but what good is a mangy old cat? Unless that cat can talk.

The talking cat tells his master that if he gives Puss a bag and a custom made pair of boots, this cat will make his owner very fortunate indeed. The lad is skeptical, but he gets Puss a bag and the famous pair of boots. Then the feline puts his crafty plan in motion.

Building a Reputation with Royalty

Puss uses his new bag and boots to catch a rabbit, a brace of partridges, and other game, taking each of his catches to the royal palace. A talking cat in fancy boots is unusual enough that Puss has no trouble gaining an audience with the king. Puss claims that each of these gifts is from the Marquis of Carabas, his master’s new and completely made-up title. The cat becomes well-known at court for his frequent and welcome visits.

A few months later, Puss tells his master to bathe in a river the same afternoon that the king and his daughter will be riding past in their coach. Puss yells out that his master, the Marquis of Carabas, has been robbed and lost his clothes to rogues on the road. Realizing this is the same Marquis who’s given him so many presents, the king springs into action and provides a beautiful suit of clothes for the lad.

The miller’s son joins the king in his coach, and the princess immediately falls head over heels for this handsome young man dressed so well. While the two royals and the fake royal are driving through the countryside, Puss races ahead of them and threatens all the farmers and workers to tell the king that they work for the Marquis of Carabas. The king is astounded that the lad owns this much good land.

Then Puss Faces One Final Foe

Puss in Boots reaches the castle where the real lord to all these lands lives: an ogre. A shapeshifting ogre to be precise. Puss sits down with this ogre (as you do) and expresses doubt that the monster can actually change into something large like a lion. The ogre becomes a lion instantly. Then Puss challenges him to turn into something small. Like a mouse perhaps? The ogre changes into a tiny mouse—and Puss promptly eats him.

With the ogre gone, the castle and all those lands now belong to the once-poor miller’s son. He welcomes the king and the princess into his new castle, and the king is so impressed that he offers his daughter’s hand in marriage. The princess certainly has no objections since she is violently in love after just one carriage ride. So the couple weds that very day.

As for Puss in Boots: “The cat became a great lord, and never again ran after mice, except for entertainment.” It’s safe to say that they all lived happily ever after.

So How Many Versions of Puss in Boots Exist?

I was surprised that this story has been told so many times in so many countries. Most versions of Puss in Boots involve a protagonist inheriting a cat, said cat gaining the attention of royalty, and the protagonist donning royal attire after pretending to lose their clothes. Whether the hero gets married before or after gaining a castle depends on the version. But most of the time either an ogre, a troll, or an evil sorcerer must be bested to take the castle. It’s always the animal sidekick who takes out the previous owner, clearing the way for the protagonist’s wealthy future.

The ingenious animal companion isn’t always a cat, by the way. Several versions of Puss in Boots feature a fox as the animal who brings their master luck, unsurprising for European folklore. Other animals that play the role of Puss are a jackal in two different tales from India and a monkey in the Philippines. But more likely than not, the animal companion is a smooth-talking cat.

But What Is the Original Version of Puss in Boots?

Most iterations of this story are from the nineteenth or twentieth century. Charles Perrault’s French version predates all of these stories since it was published in 1697. But there are two versions even older than Perrault’s, both from Italy. The first is “Gagliuso” by Giambattista Basile, published in the 1630s. This is the same guy who wrote “Sun, Moon, and Talia,” the seriously messed up original Sleeping Beauty. His version of Puss in Boots is not nearly as weird, but it has a sadder ending than Perrault’s.

Some notable differences to the story: in this version, Puss is a she-cat who catches fish to gift to the king. The story doesn’t mention anything about the cat wearing boots, but she does get fine clothes for her master by claiming that he was robbed and doesn’t have a single shirt to wear.

The king sends clothes so the boy can dine at the castle, and Puss brags about all the lands and riches her master owns. She reinforces these lies later by tricking many herdsmen and farmers into claiming that they all work for her master when the king’s men come asking. There’s no climax with an ogre in this version since the lad marries the princess first and uses her large dowry to purchase land and become a baron fair and square.

But the Story Isn’t Over

After becoming a rich man, the miller’s son thanks Puss profusely and promises that when she dies, he will bury her in a golden coffin and keep it in his chambers to remember her always. Puss decides to call the boy’s bluff and pretends to die just three days later.

Apparently the guy was all talk since he tells his wife to fling the cat’s corpse out the window. Upon hearing this, Puss jumps up and berates her master for going back on his word. The miller’s son tries to apologize, but Puss isn’t having it. Instead she throws on her cloak and leaves, never to return.

Several versions of Puss in Boots feature this final test of loyalty with the cat playing dead to see if the protagonist will honor his word. Sometimes when the cat calls his bluff, the protagonist bends over backwards to make it right. It’s unclear whether this is out of guilt or self-preservation. After all, the cat knows the truth about this kid’s origins and could easily destroy him. But in Basile’s version, Puss just quietly leaves, taking her brains and leaving the boy to fend for himself. This final gesture certainly sends a strong warning of the bitterness of ingratitude. Best be loyal to the hand that feeds you.

But There’s Still an Older Version of this Story!

Even older than “Gagliuso” is the tale “Constantino and His Cat” by Fiovanni Francesco Straparola. This version is also Italian, but it was written in the 1550s, which makes it the oldest version of Puss in Boots that I found. This tale is quite similar to Perrault’s version with two notable exceptions.

Like “Gagliuso,” this tale also lacks an ogre for Puss to defeat. Instead, it’s stated that the noble who lives in the huge castle was also bringing home a new wife when “an unhappy and unforeseen accident” causes his death. So Constantino just moves in. No questions asked. I have a theory that Puss, in true mob boss fashion, might have bribed somebody under the table to get rid of this nobleman. It just seems too coincidental . . .

Interestingly, Straparola’s tale is also the only version that spells out why Puss can talk: the cat is a fairy in disguise.

The Identity of Puss in Boots

The whole concept of Puss as a fairy actually checks out. Fae are known for being tricky and ethically ambiguous if not downright cruel. So it makes sense that Puss would be okay with all the lying and threatening to guarantee his master’s future. The majority of Puss in Boots stories have no explanation of where this clever cat came from, but some end with an enchantment on the cat breaking.

A standout example is the Norwegian story “Lord Peter.” Here, the female Puss orders her master to cut off her head after she’s secured his title and riches. The protagonist DOES NOT want to go through with this, but when he eventually obeys her, the beheaded cat transforms into a princess so beautiful that the young lad instantly falls in love. In this version, the princess the miller’s son marries is Puss in Boots. Quite a plot twist. And apparently the troll that Puss defeated is the same troll who put her under the spell. Turns out that the castle belonged to Princess Puss all along and she’s merely taking back what was already hers.

This strange twist of breaking a spell by beheading the cat shows up in several versions of Puss in Boots (also in Madame D’Aulnoy’s “The White Cat” fairy tale, which is a version of Beauty and the Beast). Kind of sadistic way to break an enchantment. But it also makes more sense why Puss would stick around to get that spell broken. This cat clearly doesn’t need her master to survive. But if Puss is a fairy, maybe the cat is under a magical contract to stay . . .

This is all speculation of course. In most versions of Puss in Boots, the cat is simply a cat. A clever talking cat, sure, but all fairy tales require readers to suspend their disbelief.

So What Exactly Is the Big Takeaway of Puss in Boots?

At a first glance, this fairy tale has an awful lot in common with the very morally questionable Jack and the Beanstalk. Like Jack, Puss in Boots has no problem getting ahead by lying, stealing, and cheating his way to success. Whoever said “cheaters never prosper” clearly never read Puss in Boots. Then again, Puss isn’t just in it for himself. His master was starving, so I suppose the cat’s intentions are pure. In most versions of the story, Puss also destroys a force of evil by outsmarting an ogre, a hideous giant known for eating human beings. It’s clear from Perrault’s stated moral that Puss in Boots is meant to be the hero:

Moral: There is great advantage in receiving a large inheritance, but diligence and ingenuity are worth more than wealth acquired from others.

So Puss in Boots is a celebration of street smarts and using your head rather than relying on inherited wealth. Quite a relevant message in Perrault’s time when the rise of the bourgeois was transforming French society. Then again, the miller’s son ends up wealthy because he inherited a clever cat rather than gaining the wealth for himself . . . But maybe I’m reading too much into it.

This Is Also a Story about Loyalty

Obviously all the versions with a loyalty test have a clear message: if someone helps you, give thanks where thanks is due. Even the king’s behavior in Puss in Boots mirrors this message. After receiving so many gifts from the Marquis of Carabas, the king is quick to help out the lad, even betrothing him to his daughter.

Then of course there’s the loyalty of Puss to his master. Even in Perrault’s version, the miller’s son was thinking about skinning Puss at the beginning. Puss could have chosen to hightail it out of there. But instead, Puss honors the miller’s wishes and sticks with his new master despite being unappreciated. Puss proves he’s willing to play the long game, even if certain moves were—ahem—somewhat morally gray. So yeah, I can see how Puss is more hero than antihero in that sense.

But no matter what version of Puss in Boots you read, there does appear to be one more theme that touches every single one . . .

The Transformative Power of Clothes

I wrote a whole article about the power of shoes in fairy tales, especially for characters down on their luck. Puss in Boots is a particularly charming example of this trope. Puss doesn’t gain his power of speech or his strategic prowess directly from the boots, but the boots are the contract that puts Puss’s plans in motion. Maybe he just wanted a pair of boots. Or maybe it was the boots that made Puss look regal enough to approach royalty in the first place. Who can say?

But what about the versions where the cat (or fox or jackal) doesn’t wear anything? Even then, there’s one plot point that appears in every single version of this story: the clever ruse of the protagonist losing his (or her) clothes and receiving royal apparel. This is the turning point in the Puss in Boots story. Because apparently if you don’t dress the part, you can’t even pretend to be noble. This aspect of the story was important enough that Perrault included a second moral for Puss in Boots:

If a miller’s son can win the heart of a princess in so short a time, causing her to gaze at him with lovelorn eyes, it must be due to his clothes, his appearance, and his youth. These things do play a role in matters of the heart.

Call it shallow, but Perrault, who spent plenty of time in French court, understood that clothes say everything about your status in society. Therefore, they play a not-so-small role when marrying above your station. Just ask Cinderella.

I’m Not Sure If Clothes Make the Man, But They Do Provide a Foothold to Rise Higher

Puss in Boots is a prime example of faking it until you make it, especially where clothes are concerned. Puss uses his boots to gain leverage in an inhospitable world. The miller’s son uses his clothes to enter into a smart match and a better life.

Back in the day when social status wasn’t fluid, a story about gaining wealth by simply wearing royal clothes was the exact wish-fulfillment people craved on a cold winter night. Maybe the cat curled up by their feet would become a talking good luck charm too . . . After all, it’s the magic found in the mundane that truly makes a fairy tale a fairy tale. ❧