It’s been decades since the classic fairy tale Jack and the Beanstalk has even crossed my mind. But I certainly remember all the good parts: spontaneously growing vines, magic kingdoms in the clouds, a hen that lays golden eggs, and the terror of a giant’s approaching footsteps. I was excited to dive into the original text of this adventure story to find out exactly how much I’d forgotten. Now that I’ve reread it, I can say with certainty . . .

Jack Is Kind of the Worst

Truly. This is the shallowest fairy tale I think I’ve analyzed so far on Snow White Writes. And that’s mostly because the main character just doesn’t have a whole lot to him. Jack is basically a one-dimensional, opportunistic jerk, my friends. But we might as well discuss how I came to that conclusion.

I will say that Jack is meant to be a stock character. Jack is a nickname version of the common English name John, and various versions of Jack show up in many modern English fairy tales. Beyond that, the concept of an unremarkable boy going from rags to riches by stealing treasure from an ogre is a story concept that is thousands of years old. This plot has repeated itself over and over again for a reason . . . but I’m getting ahead of myself.

First, What’s the Classic Version of Jack and the Beanstalk?

I’m not going to call it “the original” since this story was told orally long before it was ever written down. But British folklorist Joseph Jacobs recorded the most famous version of Jack and the Beanstalk. Jacobs was one of many scholars inspired by the Grimm Brothers’ collection of German fairy tales. He also aspired to record the oral fairy tales of England in the late 1800s.

One such tale was Jack and the Beanstalk, and since the Jacobs version is relatively unsanitized with edits and injected morality, it’s also our best bet of how people told this story while sitting around the hearth on dreary English nights.

It Starts with a Widow, her Son, and a Cow

A poor widow and her son, Jack, rely on the money from selling their cow’s milk. When the cow suddenly produces nothing, Jack and Mom are instantly in a tizzy.

The first thing we learn about Jack is that he’s tried before to get a job to help the family. But as his mother points out, “nobody would take you.” There’s no explanation as to why their neighbors don’t want a worker like Jack . . . Is the kid super lazy? Dumb? Covered in lice due to his humble circumstances? Maybe he’s just very young, but there are no references to his age in this fairy tale. For whatever reason, their only option is for Jack to take the cow to market and sell her. Presumably by lying about how much milk she produces.

Jack Meets a Mysterious Man on the Road (As You Do)

This “funny-looking old man” immediately gets friendly and asks if Jack will trade his cow for five magic beans that will grow straight to the sky by morning. The text mentions (perhaps tongue in cheek) that Jack is “sharp as a needle” for being able to count to five. We can also add gullible to his list of characteristics since Jack actually goes through with this trade before he’s had a chance to take the cow to the market and negotiate a better offer.

But hey, the old guy’s claim did end up being true, so maybe I’m being too hard on Jack. Then again, did the guy also know this beanstalk would lead Jack right to a family of man-eating giants? Is this guy on the giant’s payroll or something, keeping him well-stocked with young flesh to eat? Or was he truly doing Jack a favor to reverse the kid’s unfortunate circumstances? We’ll never know.

But I’m sure you all know what happens next.

The Beanstalk Grows Straight to the Clouds in One Night

When Jack’s mother learns that Jack has traded away their last hope for five old beans, she tosses them out the window and sends the boy to bed hungry. Of course when Jack wakes the next morning, it’s to a darker room than normal because an absolutely enormous beanstalk has sprung up overnight just as the old man said. Like any little boy would, Jack has to climb it—for hours I would presume.

This is where the story gets interesting. Because there appears to be an entire magical civilization in the clouds just hanging out above the British Isles. And it’s inhabited by giants. I should note that Jacobs’ text doesn’t initially call them giants. Instead it states that Jack encounters “a great big tall house” and a “great big tall woman” who’s married to the main villain.

And For Some Reason She Invites Jack in for Breakfast

It’s seriously unclear why she does this . . . Jacobs does mention that Jack is very polite (and persistent) when he says he hasn’t eaten since yesterday. And to be fair, he just completed the Olympic feat of climbing a sky-high plant. The lady warns him that her husband eats little boys like him for breakfast, but instead of running like a rabbit, Jack insists until she invites him in and feeds him. Before Jack is finished, the whole house shakes as the lady’s husband—sometimes called a giant, sometimes an ogre—arrives while reciting his signature anthem:

Fee-fi-fo-fum,

I smell the blood of an Englishman,

Be he alive or be he dead,

I’ll have his bones to grind my bread.

But the wife acts quickly and hides Jack IN THE OVEN before tending to her husband and gaslighting him to believe he’s smelling the boy he ate yesterday. I can’t for the life of me understand 1) why the wife does not also eat little boys, or 2) why Jack finds such an unlikely ally in her. This could very easily have been a Hansel and Gretel bait and switch to fatten Jack up and then shut him in the oven for supper. There’s no understandable reason why the giantess would save the boy’s life, but this gets at another important aspect of Jack’s character.

Jack Is Outrageously Lucky

Seriously, Jack is the luckiest son of a gun you will meet in ANY fairy tale. Just about every aspect of his story works out well for him, even when he makes questionable decisions. After taking a wildly bad deal for his cow, it turns out that the old man’s scam wasn’t a scam at all. Plus this fast-growing beanstalk, which really shouldn’t have benefitted the kid at all, turns out to be his ticket to riches through another series of lucky breaks.

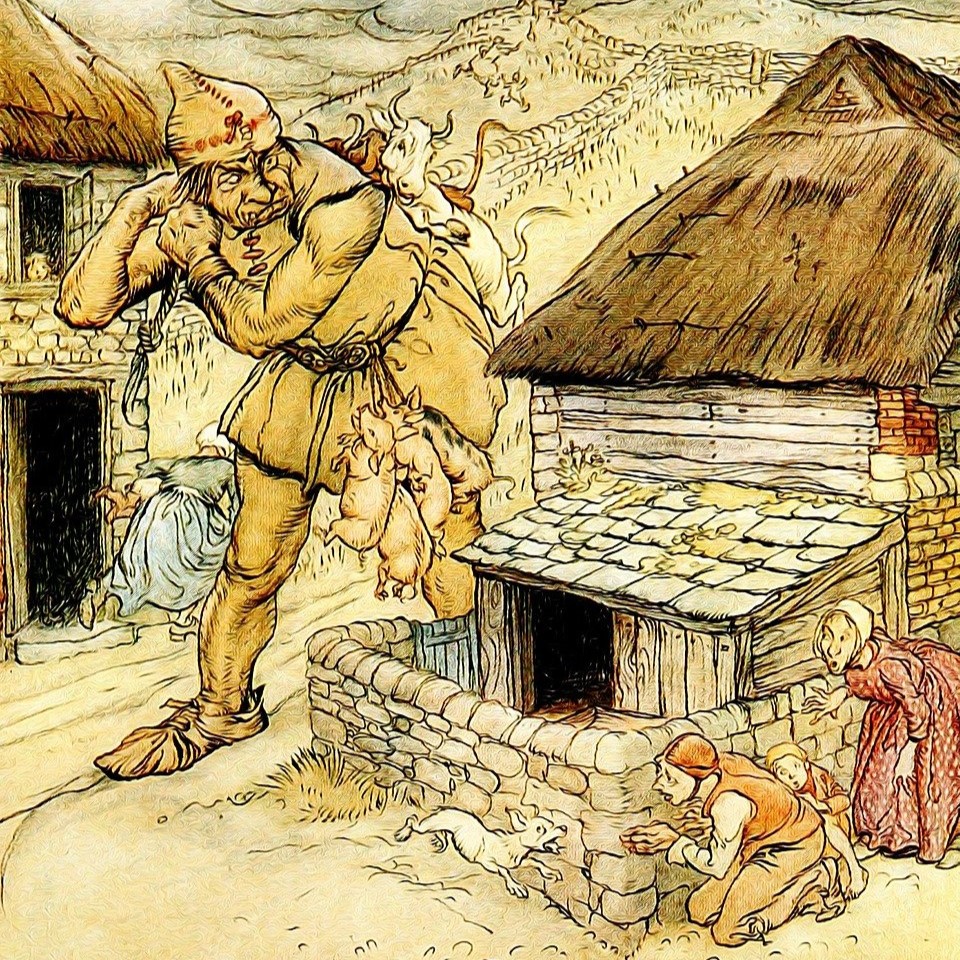

After surviving the giant thanks to his newfound giantess friend, Jack escapes safe and sound—and repays her kindness by stealing a bag of the giant’s gold. I get that Jack and his mother are desperate and all that, but seriously? This giantess fed you and saved your life, and your response is to steal from her? I guess no good deed goes unpunished.

And So Begins Jack’s Life of Crime

You would think that Jack would just take his gold, start a shop with his mom, and call it a day. But can he resist the chance to return to the giant’s house and steal something else? Of course not. And once again, what looks like a horrible decision on Jack’s part actually pays off. The giantess, who fully suspects that Jack stole that bag of gold, still invites him in for a meal (really?), still hides him in the oven when her husband comes home (why?), and still doesn’t rat him out! When Jack sees the giant’s hen that lays golden eggs, his sticky fingers snatch it faster than you can say “dirty thief.”

At this point, Jack now has a sustainable source of income and is set for life. SURELY he wouldn’t go back into the den of two giants who are now aware that this boy has stolen twice from them . . . Except that Jack does. He doesn’t approach the giantess this time. Instead he hides in one of the copper pots and then makes off with a magical golden harp. Not because he needs the thing, mind you. He just wants it and has apparently grown very bold in his greed.

The Giant Is More Victim than Villain at this Point

I suppose anyone who eats children in fairy tales is a pretty solid villain. But can you blame a guy for eating nosy children who trespass in his house? The text mentions nothing about the giant hunting down little boys to eat, so it seems like these giants just want to be left alone in their cloudy paradise. Jack is the one who keeps crashing their crib and repaying hospitality by stealing stuff.

So yeah, when the giant starts chasing the little reprobate down the beanstalk to retrieve his stolen harp, I’m kind of on the giant’s side after this series of events. What did Jack think was going to happen? But once again, Jack very luckily gets a head start down the stalk and has his mother fetch an ax for him. He chops the beanstalk down, and the giant dies. All ends happily for Jack and his mother, who become very rich indeed from Jack’s spoils. Then Jack randomly ends up marrying a princess because why not?

And the Message: It Pays to Steal?

I wish I was joking, but that’s kind of all there is to Jack and the Beanstalk. It’s not meant to teach great morals. It’s an adventure story about a boy who starts out poor and against all odds becomes rich. To be fair, that’s the main message of many classic fairy tales: that it’s possible to social climb out of the depths of poverty and become a royal. That concept of the underdog coming out on top was every peasant’s dream long ago. And frankly, it was way more of a fairy story back in a medieval economy than it is today.

Still, Jack isn’t exactly brimming with outstanding qualities. He’s an unemployed gullible boy who lies and steals. Sheer dumb luck seems to be the biggest factor to his happy ending, but other versions of Jack and the Beanstalk sprinkle a little morality in there.

The Moralizing of Jack and the Beanstalk

Andrew Lang’s version of this fairy tale is the best example of how Jack and the Beanstalk was sanitized to teach children how to be good. There are plenty of wholesome little lessons scattered throughout, like when Jack is climbing the beanstalk and starts tiring half way. Despite wanting to turn back, he keeps on climbing because “he was a very persevering boy, and he knew that the way to succeed in anything is not to give up.” Yep. I think we got that lesson.

But the biggest change in Lang’s version is the colorful backstory. When Jack first climbs the beanstalk, a fairy in disguise tells him that the giant’s castle once belonged to a great knight. The giant killed this knight and took all his possessions, but the knight’s lady and infant son escaped with their lives. You guessed it: Jack and his mother are actually nobles, and therefore everything in the giant’s castle is actually Jack’s. This little detail makes it quite easy to justify all the stealing since Jack is just reclaiming his murdered father’s stolen wealth. The lad becomes downright courageous to undertake this mission.

This context also makes the giant a more legitimate villain who has wronged Jack’s family and fully deserves the treatment he receives. All of these story choices make Jack’s thievery feel like it was for a better cause than mere selfishness.

But Honestly? The Joseph Jacobs Version of Jack Is Truer to the Point of the Character

When people were orally telling Jack and the Beanstalk, they weren’t attempting to teach children to be good or spread Christian values. Nothing of the sort. Original fairy tales are gritty, realistic, and entertaining. And they certainly weren’t tailored for kids back in the day (though that’s a separate discussion entirely).

The whole point of Jack’s adventures is escapism. Pure wish fulfillment of poor people telling stories and hoping for some lucky breaks that lead to riches and a life without toil. The entire point of this story was to weave a good old-fashioned yarn about giants in the sky, heart-pounding risks, and a boy just foolhardy enough to take his fate into his own hands. Stories like this one were probably a welcome break from a bland existence of never having enough to eat.

In a Way, Jack Represents All of Us

How many stories are there about regular, unremarkable people ending up happy and rich? Jack is an English stock character, the stereotypical everyman. He’s the untamed child in all of us, wishing for a happier, easier life. Perhaps magical opportunities will come to YOU for a change, maybe in the form of five ordinary-looking beans. And preferably in time to save you a long, dusty trip to the market.

Jack may be an awful character, but his flaws are also the kind that everybody can understand. Because what kid hasn’t dreamed of adventure, an easier life, and a complimentary breakfast amongst the clouds? ❧