Like many fairy tale figures, it’s hard to say when I first encountered Baba Yaga. I remember reading about her in stories and learning about her as early as elementary school. She made appearances in animated media I saw, most notably in an episode of Arthur on PBS. She’s certainly the inspiration for the antagonist of Miyazaki’s breathtaking Spirited Away. I can even detect her influences in the famous Howl’s Moving Castle, a whole story about a house that moves around of its own volition. But for a long time, I thought Baba Yaga was just the Russian version of the witch from Hansel and Gretel: a wicked old crone who lives in the woods and eats little children who wander too close.

Upon closer inspection, Baba Yaga is far more complex and distinct than your average cannibal witch. In fact, she’s downright contradictory depending on the story. After taking a deep dive into Baba Yaga lore, I can say with certainty that this particular figure is quite special in the lineup of fairy tale witches in the woods.

First of All, What Is a Baba Yaga?

Until recently, I was under the impression that Baba Yaga was a singular legendary witch from Russia—i.e., THE Baba Yaga. But apparently Baba Yaga is less of a singular character and more of a species. Think vampires or sirens. She appears in Slavic illustrations and stories from Eastern Europe and Russia in the seventeenth century, but of course she was a part of oral tradition much longer than that. Scholars are unclear on the exact translation of her name, but “Baba” seems to mean “old woman” or “grandmother.” “Yaga” is more ambiguous and can mean anything from “snake” to “wicked” to “horror.” The gist is that she’s a dangerous woman, an unsettling combination of brutality and familiarity.

If you stumble across a Baba Yaga, you’re running into just one of such witches. Sometimes heroes stumble across a trio of three Baba Yagas living together. But no matter which witch you meet, all iterations of Baba Yaga have several things in common. First, she lives in the woods. And like the famous antagonist of Hansel and Gretel, she is famous for devouring children. Stories often reference her tendency of kidnapping and eating babies.

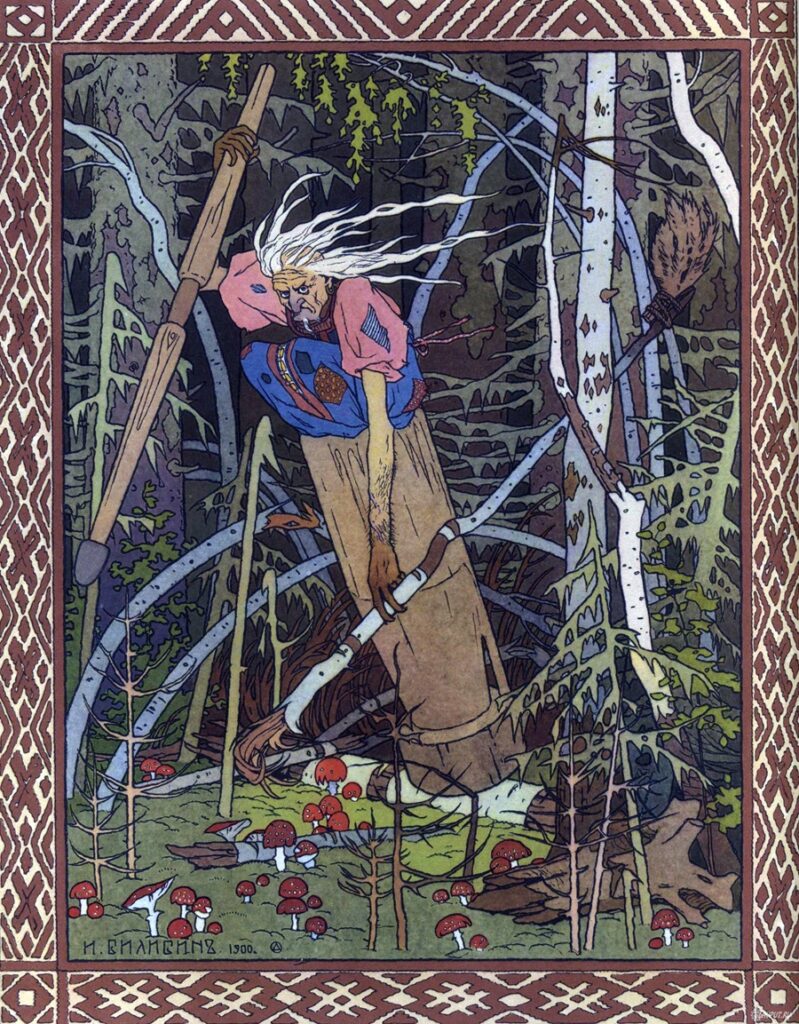

Even without such a gruesome hobby, Baba Yaga’s appearance is quite horrifying. Often described as “bony legged” and repulsive, she has the haggard face of an ogress and iron teeth for devouring young flesh. She’s also renowned for her long prominent nose that apparently touches the ceiling when she sleeps. All the better to sniff out her unfortunate victims.

What’s a Witch Without Her Accessories?

There are several knick knacks that Baba Yaga is known to possess. While western witches fly around on brooms, Baba whizzes across the forest floor in a flying mortar and pestle. She does carry a broom, but she uses it to sweep away her tracks behind her flying mortar, making herself harder to find as she returns home from hunting for young flesh to eat. Baba Yaga is also known to possess an enormous kitchen stove that stretches from one side of her house to the other. Her visitors often find Baba lying across said stove, a constant reminder of where she cooks up her victims.

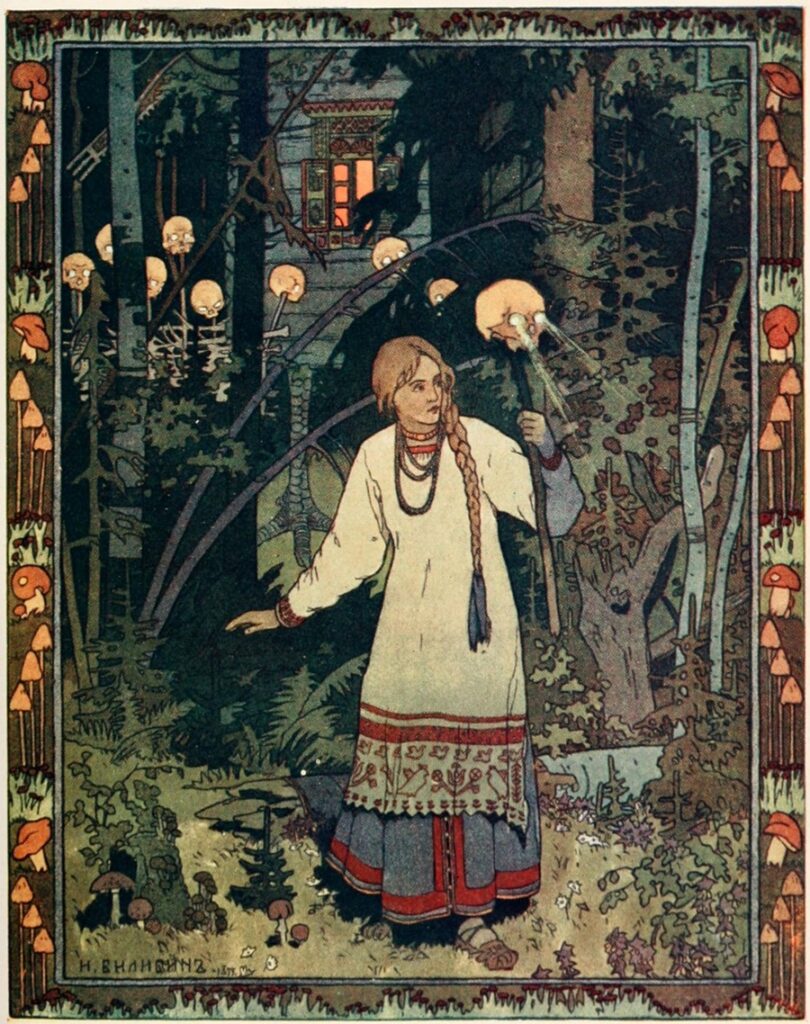

But the most iconic possession of Baba Yaga is her cottage in the woods. This hut is surrounded by a fence of human bones, and the entire house is perched on top of chicken legs that allow her home to wander the woods whenever she desires. Several stories reference her house spinning infinitely on top of the chicken legs until a brave visitor commands it to stop at the front door. Super weird. Super random. And if you’re a fairy tale enthusiast like me, the weirdness is exactly what I came for.

For the record, there are many theories about why Baba Yaga lives in a house on top of chicken legs. The most interesting hypothesis I found was that this leggy house resembles Neolithic burial practices of binding bodies and placing them up on stilts to dry out before burial. This certainly jives with Baba Yaga’s associations with death and the possibility that she is a goddess of the underworld.

But Baba Yaga Isn’t Just a Gluttonous Wicked Witch

There are literally thousands of stories that feature Baba Yaga. Though I can’t possibly reference all of them, let’s explore the most famous tales that you’re likely to find and the many depictions of this infamous Slavic witch.

There are plenty of stories where Baba is a simple antagonist for the hero to outsmart. A prime example is the Russian version of Cinderella—“The Baba Yaga.” In this fairy tale, a jealous stepmother sends her beautiful stepdaughter to the Baba Yaga, hoping to eliminate the child without her father’s knowledge. Thankfully, the girl is smart enough to visit her kind aunt first. This fairy godmother figure gives her all the advice and gifts she needs to visit Baba Yaga unscathed. Baba asks the girl to weave at a loom while the witch makes plans to cook her up, but Cinderella gives food and presents to Baba’s servant, her animals, and the sentient hut doors and trees of the forest. All of them help her escape safely despite Baba Yaga pursuing Cinderella in the magical mortar.

The message of this tale is pretty obvious: if you’re good and kind to everyone (and happen to have an aunt who knows about Baba Yagas) you’ll end up just fine. This moral is reinforced by Baba Yaga’s cruel treatment of her underlings, who are not loyal to their harsh and selfish mistress. Here at least, Baba is a one-dimensional villain only interested in her supper.

In Other Versions, Baba Yaga Is There to Test the Hero

Instead of hunting down people to torment, Baba Yaga is far more likely to be a chill, stay-at-home kind of witch who will test the valor of anyone brave enough to visit her. Baba Yaga usually won’t bother you unless you bother her. A notable exception is this story about a boy named Hryshka who Baba Yaga kidnaps from his own garden. But in every other story I found, the protagonist must seek out Baba Yaga.

It’s quite standard for protagonists to escape Baba Yaga unscathed, but she’s just as likely to let someone go as to pursue them. In many, many cases Baba Yaga gives the protagonist domestic chores to complete. If you please her, she will reward you with gifts and much-needed advice. Displease her and the ending won’t work out in your favor.

A great example is “The Stepdaughter,” which is quite similar to the French fairy tale “Diamonds and Toads” (or “The Fairies” as Charles Perrault titled it originally). Once again, an evil stepmother banishes her stepdaughter to the woods to be devoured by Baba Yaga. In this adventure, Baba gives the girl some impossible house chores to complete by morning or be eaten. The daughter despairs, but she’s kind to the mice in Baba Yaga’s hut. The little creatures help her complete the tasks, and Baba Yaga sends the girl back home with beautiful clothes, riches, and a horse-drawn carriage. Upon seeing these gifts, the evil stepmother sends her own daughter to Baba Yaga. When this girl is rude and lazy, Baba eats her up and sends her home as a bag of bones. How’s that for a lesson?

Baba Yaga’s Visitors Aren’t Always Female

In another famous Baba Yaga story, an ogre named Koshchei the Deathless kidnaps Prince Ivan’s wife. The prince must seek out a Baba Yaga to gain a horse fast enough to catch the ogre, and Baba tells Ivan to watch over her three mares for three days to earn his horse. Of course trickster Baba instructs her horses to run away so she can eat the prince. But with some magical assistance, Ivan completes the task without issue. Not trusting Baba Yaga to keep her word on letting him go, Ivan steals the horse he earned in the dead of night, which earns him a hot pursuit with the mortar and pestle. In this tale, the pursuit ends when Baba Yaga drowns in a river.

Baba’s trickster tendencies seem to be a running theme of her stories. While it’s true that she rewards those who please her, her tests are always tilted in her favor. Without magical intervention, the protagonists would all end up as her dinner, which is certainly Baba’s intention. But at the same time, she’s generally known to keep her word when she says she’ll let you go. Maybe Prince Ivan shouldn’t have been so distrustful.

Sometimes Baba Yaga’s Rewards Go Above and Beyond

The most well-known story featuring the Baba Yaga is “Vasalisa the Beautiful,” one of the most famous Russian fairy tales. And it displays some of the most interesting aspects of the Baba Yaga. This story starts with a little girl named Vasalisa and her merchant father. Vasalisa’s mother is dying, and her final gift to her daughter is a magic doll. If Vasalisa needs help or advice, all she has to do is feed the doll and it will serve her. Pretty nifty.

After his wife’s death, the merchant remarries a widow with two daughters of her own. The evil stepmother and stepsisters despise Vasalisa and work her to the bone, but the girl only grows in beauty. Whenever the work proves to be too much, Vasalisa feeds her magic doll and receives help to complete her work. Her stepfamily’s jealousy of Vasalisa consumes them. One stormy night when Vasalisa’s father is away on business, all the fires go out. In some versions, the stepsisters put the fire out on purpose to get rid of Miss Perfect. The ploy works since the stepmother sends Vasalisa into the forest to ask Baba Yaga for a light.

Enter Baba Yaga!

Vasalisa is terrified, but her magic doll assures her that everything will be alright. She finds Baba Yaga’s house surrounded by glowing human skulls and turning continuously on top of two chicken legs. Baba Yaga welcomes her inside and gives her some chores to do in exchange for the light her stepmother requested. If Vasalisa fails to complete any of these tasks, Baba will eat her up. But with the help of her doll, Vasalisa passes the test easily.

Baba Yaga is actually impressed with the girl’s pluck and rewards her with a human skull with glowing eyes as her light source. Creepy . . . but certainly memorable. Vasalisa returns home with her glowing skull and her doll safely tucked in her pocket. When the skull sets eyes on her stepfamily, it burns up the stepmother and stepsisters, leaving Vasalisa as the lone survivor.

Vasalisa goes to live with a kind old woman and eventually catches the attention of the Tsar. He is so enamored by her beauty that he marries her. When Vasalisa’s father FINALLY returns (nice of you to show up, Dad), he’s thrilled to pieces that his daughter has secured such a fine match.

For Vasalisa, the Baba Yaga Becomes a Benevolent Benefactor

While many heroes secure magical gifts from Baba Yaga, Vasalisa’s is unique. It becomes not only a protection from the darkness, but an escape from her abusive servitude. Of course we can question the means of this escape. Baba Yaga clearly has questionable ethics. She has zero qualms with murdering people, but by eliminating Vasalisa’s stepfamily, Baba sets the heroine free to achieve her happily ever after.

This is actually a common theme of Baba Yaga stories. Most protagonists who encounter Baba end their stories by getting married or reuniting with a lost spouse. There’s a lot of theories about Baba Yaga’s role of training young people for the transition into marriage. Why else would she give them so many domestic chores to complete under threat of death? Apparently Baba Yaga is a threshold guardian of marriage who teaches young people to submit to difficult expectations, complete manual labor, and keep their commitments.

Once a protagonist faces Baba Yaga, they’re ready to grow up and move on to the next chapter of life.

Baba Yaga Is a Paradox of the Natural and Unnatural

Baba Yaga’s role in coming-of-age stories brings up another fascinating aspect of this character. While there’s so much about her that’s unnatural and unsettling, she’s also a common symbol of nature itself. Many scholars see her as a Mother Nature stand-in who has control over the elements. We see this in “Vasalisa the Beautiful” when the heroine encounters three mystical riders in the woods: a white rider, a red rider, and a black rider. Later in the story, Baba explains that these riders are the bright day, the red sun, and the dark midnight. In other versions the three riders symbolize sunrise, sunset, and the night. But the point is that Baba Yaga describes these magical riders as her servants who she commands. A witch who can control the sun itself? Wow.

This is just one example of Baba Yaga as a god-like figure, a deity of natural phenomena. Like nature itself, Baba is both powerful and cruel. Baba Yaga is part of the process of children growing up, but she’s also the deciding factor if adulthood never arrives. If she decides to eat someone, they’ll never cross that threshold. Baba is associated with death and the capriciousness of whether children survive the harsh realities of sickness, hunger, and danger. At her heart, Baba Yaga is brutally unpredictable, although she is known to keep her word in most stories.

Of course, it’s rather ironic that a figure like Baba Yaga would represent the natural world when so much about her is wildly unnatural. An old ugly hag living alone in the woods? A woman with iron teeth, a cannibalistic appetite, and an enchanted house on legs? Could there be anything more unnatural than that?

The Inconsistencies of Baba Yaga Are Just Part of Her Lore

Baba is notoriously difficult to categorize because her fairy tales are so blasted contradictory. In some tales she’s a deity who controls the elements. In other stories, nature turns against her as rivers and forests bring about her untimely death. Some stories depict her as invincible and all-knowing. Others show her vulnerabilities to trickery. There are stories where she’s a terrifying ravenous monster. And there are stories where she’s almost maternal, a mentor who passes on her magic to apprentices who do quite a bit of good in the world. Again and again, Baba Yaga toes a fine line between life and death. Between good and evil. Though chaotic neutral is probably the best way to describe her.

So I guess there’s no straight answer of whether Baba Yaga is a benefactor or a villain, a mother or a monster. As I was researching Baba, every single claim I found about her was eventually debunked by a story I discovered. I think this is the most unique aspect of Baba Yaga: the complete lack of rules by which she lives in her own lore. It’s incredibly confusing that Baba Yaga appears to be both everything and nothing in Slavic folklore. She’s in thousands of stories and also presents thousands of faces in her fairy tales. But there’s one characteristic that she always has . . .

Baba Yaga is a Figure of Transformation

Perhaps this is why Baba features is so many stories of young people growing up and grownups making recompense for a mistake. It’s utterly ironic that such a wild character would be the teacher of responsibility. But then again, Baba Yaga is both a wild woman AND a domestic one. She seems to represent the conflict between unbridled human urges (rage, hunger, sexual desire, and pride) and our very human need to submit to reality and accept our destinies.

Perhaps it’s the complicated nature of humanity that makes Baba Yaga the perfect matriarch to teach us all about how life, nature, and consequences really work. At the end of the day, she’s powerful, terrifying, and commands respect wherever she appears. It’s really no wonder she’s become a feminist icon. ❧